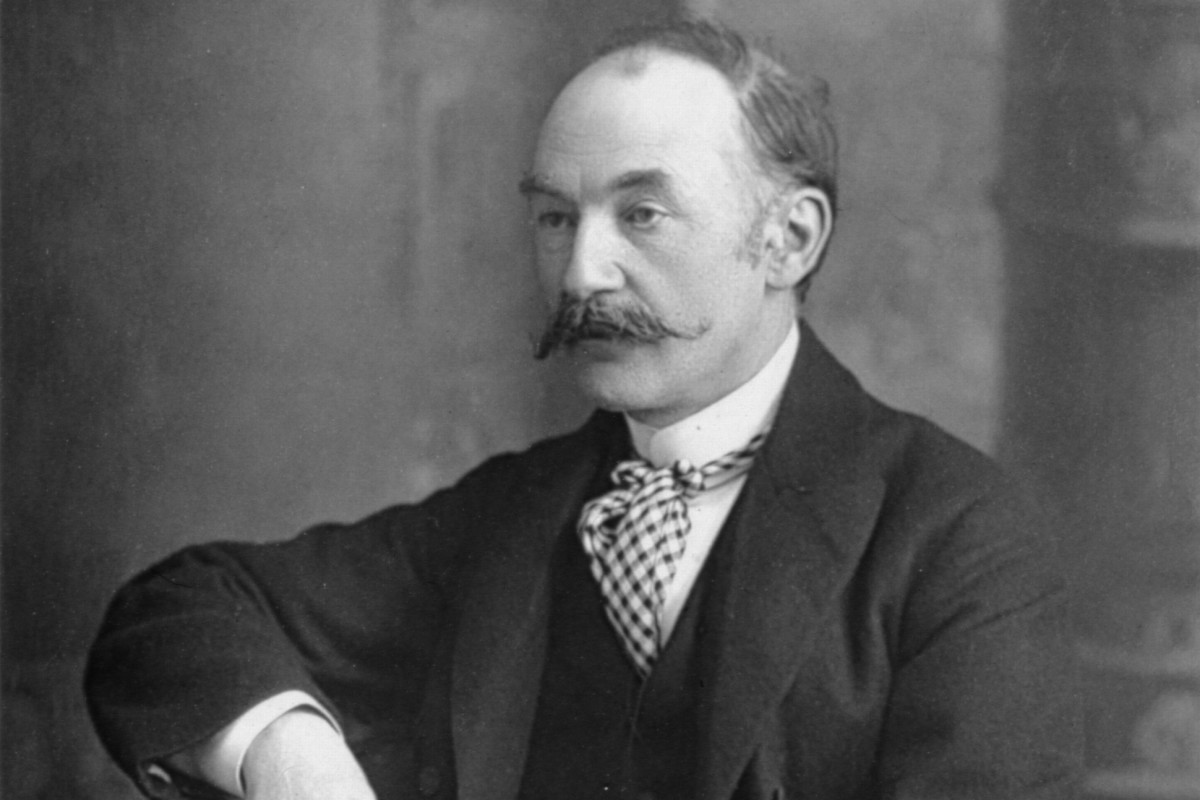

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 1888 – 4 January 1965) was raised to see his destiny in terms of a life dedicated to the highest cultural ideals, manifested in an ethic of service through established social and cultural institutions. Eliot was an essayist, publisher, playwright, literary and social critic and one of the twentieth century’s major poets. He was born in St. Louis, Missouri to an old Yankee family. However he emigrated to England in 1914 (at age 25) and was naturalised as a British subject in 1927 at age 39.

Eliot attracted widespread attention for his poem The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915), which is seen as a masterpiece of the Modernist movement. It was followed by some of the best-known poems in the English language, including The Waste Land (1922), The Hollow Men (1925), Ash Wednesday (1930) and Four Quartets (1945). He is also known for his seven plays, particularly Murder in the Cathedral (1935). He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1948, for his outstanding, pioneer contribution to present-day poetry. For a poet of his stature, Eliot produced a relatively small number of poems. Typically, Eliot first published his poems individually in periodicals or in small books or pamphlets, and then collected them in books.

About the poem –

Ash-Wednesday is the first long poem written by Eliot after his 1927 conversion to Anglicanism. Published in 1930, it deals with the struggle that ensues when one who has lacked faith acquires it. Sometimes referred to as Eliot’s “conversion poem”, it is richly but ambiguously allusive, and deals with the aspiration to move from spiritual barrenness to hope for human salvation. Eliot’s style of writing in Ash-Wednesday showed a marked shift from the poetry he had written prior to his 1927 conversion, and his post-conversion style would continue in a similar vein. His style was to become less ironic, and the poems would no longer be populated by multiple characters in dialogue. His subject matter would also become more focused on Eliot’s spiritual concerns and his Christian faith.

Eliot had needed professional help during the composition and editorial process while writing the poem, for ailments that were essentially emotional and psychological. Clearly, the disaster of his marriage had much to do with this. Under these circumstances, the Church seemed to offer something – both an end to the emotional pain he felt and a new beginning. He explored the possibility of conversion in a new series of poems from 1925 on, culminating in his greatest work of this period, Ash-Wednesday (1930). For others, it would have been difficult to understand the significance of Ash-Wednesday in Eliot’s evolution as an artist.

Was Ash-Wednesday a genuinely Christian poem or was it one more elaborate persona in a life of sustained role-play?

He never forwent the practice of impersonality in his poetry in order to speak in his own voice, even as he was undergoing the tectonic shift in religious sensibility that is so well enacted in Ash-Wednesday. Yet there are situations that he dramatizes in his poetry and plays which carry autobiographical resonances. His recourse to the dramatic monologue made it possible to deflect more easily what he would have considered the wrong type of critical interest in his work. Ash-Wednesday is still based on a set of literary sources. In the first line we hear Guido Cavalcanti’s ‘‘Perch’io non spero di tornar gia mai . . .’’ as well as Lancelot Andrewes’s Ash Wednesday sermon of 1619. However, the learning the poem wears is narrower and more local. It derives from mainly English and Anglican sources with the exception of the Italian trecentisti, poets from fourteenth-century Tuscany. There are references and allusions to Shakespeare’s sonnets, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, the Hymnal, the language of the Thirty-Nine Articles, the Anglo- Catholic Prayer Book, the Cavalier devotional tradition, and, of course, Dante. The poems that make up the Ash-Wednesday sequence speak with greater directness and simplicity than had been Eliot’s practice in the past.

His famous obscurity and difficulty was replaced by a straightforwardness that was meant, perhaps, to be disarming, to establish his bona fides in the matter of his new affiliations. Eliot, better than anyone else understood that he had his own previous reputation for speaking in masks, to overcome.

Eliot’s poem is devotional, to be sure, but it does not follow the typical pattern. Ash-Wednesday’s language is indebted to the reserve, humility, and economy of expression to be found in George Herbert.

Moreover, Eliot’s poem does not dramatize the encounter with the divine as the central matter of the poem. Rather, Ash-Wednesday must be seen as working out the tension between matter and spirit, between the sensuous and spiritual bodies. To some extent, the part of our being that is earthbound and takes in the world through our senses must be occupied by emotions, feelings, and ideas, by ritual and ceremony, in order to allow the spirit to contemplate and ascend through the agency of an intercessor, in this case the Lady, toward a glimpse of the divine in a timeless moment. This glimpse, or even potential union with God, does not occur in the poem but is conveyed by what the poem cannot yet say. What appears in the material text is movement toward what a mystical tradition might see as the appropriate annihilation of the sensuous body in order to release the ethereal spirit into the realm of God’s light. But this is not Eliot’s goal. Eliot is far more complex in his thinking; after all, the obliteration of the sensuous body endangers more than the calming of lust or other purely physical desires. It imperils the very art he has devoted his life to making. Eliot’s goal is much more subtle. Ash-Wednesday pushes toward it, but he will not bring it entirely to light until Four Quartets.

The true mystery of the Christian faith lies in the concept of Incarnation. Ash-Wednesday explores this central Christian belief. It can be brought to the light only by image and symbol, by invocations of nature and by their negation. The title, Ash-Wednesday, refers to one of Christianity’s holy days. In the Ash Wednesday Mass the materiality of the body is acknowledged and in the very same gesture redeemed by the Christian symbol of eternal life. The priest uses ash to make the sign of the cross on the believer’s forehead, with the words, ‘‘Remember, man, that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shall return.’’ Ash-Wednesday defeats the power of horror, not by separating the spirit from the body, but by offering true redemption, namely the divine spirit incarnated in human form.

Ash-Wednesday offers a personal narrative of recognition, acknowledgment, and change by a speaker who has already affirmed a faith but who needs to understand the human or existential dimensions of belief. That is why Ash-Wednesday begins with the halting, stammering voice of an abject humanity.

The motif of ‘‘turning’’ is crucial in completing the process of recognition and acknowledgment. The poem defines the process of construing a renewed subjectivity, now more fully aware of its fateful encounter with the divine spirit. The abject is not erased by this widening of consciousness; it is simply put in its proper place. Part II of the poem begins with an evocation of the body devoured by animals, ‘‘three white leopards,’’ who have ‘‘fed to satiety’’ on the speaker’s legs, heart, liver, and brain. They have left ‘‘bones,’’ ‘‘guts,’’ the ‘‘strings of my eyes,’’ and the ‘‘indigestible portions’’ of the body. They left the subject in disarray, fragmented, and deeply anxious. In Ash-Wednesday their power to disturb is not entirely diminished, but now there is a counter-movement and its proper form is prayer.

The whole prayer in Part II introduces paradox as the rhetorical form of the reborn subject, in recognition of the possibility of two truths existing as one. The Rose in the garden symbolizes this state rather well. It is, of course, a traditional symbol, but it helps to think of a real rose as well as the Rose of literary convention. The Rose of literature often symbolizes the perfection of an ideal love.

Part III of Ash-Wednesday dramatizes the relinquishing of mastery in the figure of the spiral staircase and the ascent of the subject toward a new life. Although the ascent is spiritual, the struggle on the staircase is primarily moral. In Part IV he acknowledges that the ‘‘fiddles and the flutes’’ must be borne away. The new regime brings restoration and redemption from pain and despair. But it does not erase the pain. Indeed, in Part IV we are asked to be mindful (‘‘Sovegna vos’’) of the hurt of one in Dante’s Purgatorio (Canto XXVI), Arnaut Daniel, the Provencal troubadour.

Part V backs away slightly from the personal engagement of the previous four parts to meditate on the status of the word of God, the Word in short, in a world where it is ‘‘unspoken, unheard’’. That the Word is not visibly potent in a secularist world may be a shame, but it is not fatal to the Word itself. The presence of the Word is not harmed by the fact that most are deaf to it. The poem acknowledges both the presence of God, even in his seeming absence, and the Word as revelation of His presence.

The final part of the poem returns us to the theme of transformation and to the voice of the uncertain supplicant. But instead of the causal relationship suggested by ‘‘Because I do not hope to turn again,’’ the restatement makes a subtle shift in responsibility. ‘‘Although I do not hope to turn again’’ moves from causality to concession. The subject is now better placed to accept the work of grace. He is able to see from ‘‘the wide window’’ something of the beauty of the world and a new lyricism comes into the text, ‘‘white sails . . . seaward flying,’’ ‘‘Unbroken wings’’ instead of ‘‘merely vans to beat the air’’ in Part I. The note of hope modulates into a quickening recovery from the despair with which the poem began. The prayer to the ‘‘Blesse`d sister, holy mother’’ asks for help in avoiding the self-mockery of falsehood and suffering of separation. The vision at the end is not transcendental; it cannot be defined as the desire to escape from the world into the pure bliss of the spirit. It was the Incarnation now put forward as the real meaning of faith. We cannot escape our human fate, but we are vouchsafed glimpses of holiness in the midst of the encompassing tragedy. This is not a special trick of the eye, it is what we see as an integral part of the reality we all share, if . . ., if we care to look. And the concrete reality that Eliot faced in the 1930s was not an ideal abstraction invented to house the new spiritual order. It was England and his life there in which the hidden order of grace moved.

Dear Readers- If this summary/analysis has helped you, kindly take a little effort to like or +1 this post or both. Make sure you like Beamingnotes Facebook page and subscribe to our newsletter so that we can keep in touch. We’ll keep informing you about stuffs that are really interesting, worth knowing and adds importance to you.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight

Yes it really helped me. I am very interested in having more help in other topic also.

a very thorough and illuminating analysis thank you for your helpful efforts