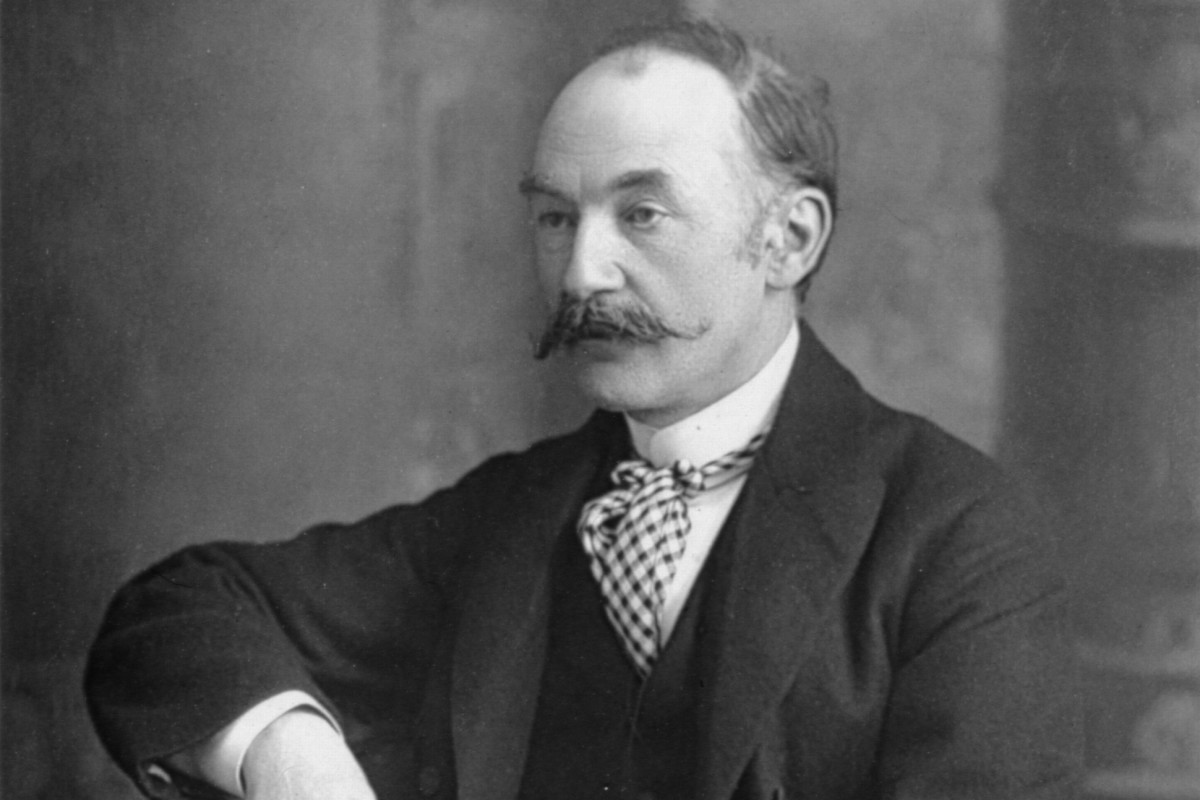

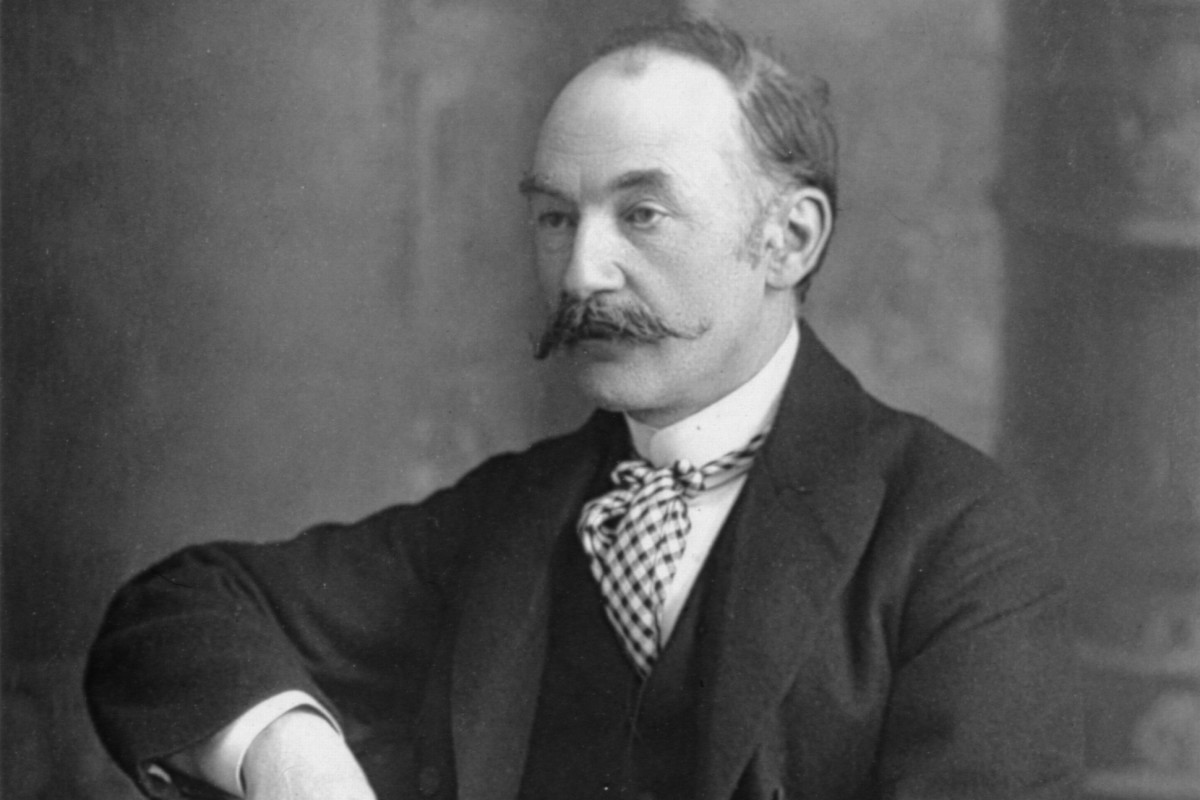

“The Oxen” is a poem by the English novelist and poet Thomas Hardy. It relates to a West Country legend: that, on the anniversary of Christ’s Nativity, each Christmas Day, farm animals kneel in their stalls in homage. It was first published in December 1915, in the London newspaper The Times

The Oxen Thomas Hardy Analysis

The poem The Oxen opens with the first two stanzas referring to the childhood memory, and Hardy uses words like “flock” to create the rural atmosphere. The words “meek mild creatures” are not only descriptive of sleepy, warm cows gently chewing the cud in their “strawy pen” but are also reminiscent of Charles Wesley’s children’s hymn. There is a tendency among young children to believe what they are told, hence the final two lines of the second stanza. The third and fourth stanzas take the reader forward to the present with the poet considering the contemporary views of himself and others. Hardy still had some belief in the supernatural elements as seen through the use of spirits and ghosts but by the time of writing “Oxen,” he had abandoned all traditional Christian beliefs.

He, therefore, states that, although he no longer swallows the story without question, in the way that he did as a child, he would not dismiss it out of hand now that he is an old man.

One must ask why Hardy is “hoping it might be so”. The answer is sure that it is not so much that he wants to test the truth of a superstitious belief, but that he wants to journey back to his childhood and relive an old memory. There is also the direct reference in “our childhood used to know”.

There is a wider “innocence and experience” message here. The old man knows the truth, but he still has a desire to return to a state of innocence, albeit more in hope than expectation. Seen from afar, in terms of years, childhood can be regarded as a safe place in which there are no doubts and everything seems ordered and “right”. Today, adults still play the “Santa Claus” game and go through the same motions that they did when they were children. Hardy’s poem hence goes back to old certainties at a particular time of a year.

“The Oxen” was published in 1915 Christmas Eve, which meant that it is not only Hardy who has left the embers in hearthside ease of his childhood. The fire by which he and the others sat then had burned down to its embers; it was dying. A whole way of life was dying, as the young men in the trenches of the First World War and their grief-stricken parents were discovering. Life would never be the same.

The Oxen by Thomas Hardy Theme

The poem The Oxen begins with a scene where everyone is sitting ‘By the embers in hearthside ease.’ It is a quiet, very comfortable scene, both physically and intellectually. The embers are the glowing pieces of wood or coal in a dying fire, giving out a considerable warmth but without the energy of leaping flames. Although Hardy does not describe it directly, there would be a gentle light on the faces of the men sitting around the fire. The rhyme of knees with ease suggests to me that the men are secure in their belief in the old folk-tradition – they are at ease with the idea.

The group round the fire are presumably somewhere deep in the country, for Hardy uses the word ‘flock’ instead of a group. However, far from sounding patronizing about the intellectual powers of country yokels who would believe this kind of thing, Hardy underlines the ease, the comfort, of these simple beliefs in the next verse:

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen;

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

The sense of certainty is continued here, and not only in the meaning of the words: ‘We pictured’; ‘Nor did it occur to one of us there / To doubt’. Just as the end- stopped, a line that opened the poem added to the certainty, so do the run-on lines in this second verse. They give the sense of ease in the belief – with no cesuras to jolt the belief.

In stanza three, Hardy shifts his focus to ‘these years.’ The poem was published in The Times on 24 December 1915, when the First World War had been raging for over a year. Historically, ‘these years’ of slaughter were much worse even than the years of the Second Boer War that Hardy had depicted in such tragic and despairing poems as A Christmas Ghost Story, At the War Office London and Drummer Hodge. So both from the viewpoint of the World War and from the viewpoint of Hardy’s own doubts and skepticism after living for 75 years, it is true that

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years.

Hardy has moved into the present, in a conditional sort of way, ‘would weave.’ ‘Weave’ is a wonderful word to have used – originally he wrote ‘believe’ and he modified it later to ‘weave’. For one thing, weaving is a traditional cottage industry, so it is another connection to traditional country folk-tales and homespun ways. For another, weaving is literally making a fabric by crossing the threads in the warp (lengthwise) and weft or woof (across); if you interlace the threads in this way, you are including all sorts of different elements into the fabric as you weave back and forth. Figuratively – and the word has been used figuratively for centuries – weaving has associations with something that may not be true, so it is an apt word for a folk tradition.

The last verse contains not only the hoped-for truth of the childhood belief but also reverts to the comforting dialect words of the country childhood, ‘barton’ and ‘coomb’. ‘Barton’, in Dorset dialect, means outbuildings at the back of a farmhouse, and a ‘coomb’ is a little valley. ‘Coomb’, the well-known word of childhood, rhymes uncomfortably with ‘gloom’, the adult’s unhappy state of mind. The certain knowledge of childhood ‘our childhood used to know’ rhymes jarringly with the adult’s uncertain hope ‘hoping it might be so.’ It is, perhaps, Hardy’s version of ‘Dover Beach’.

The Oxen by Thomas Hardy Tone

The tone and rhythm play a major role in all of Hardy’s poems and “The Oxen” is not an exception. The rhythm of the ballad-like quatrains varies. There is a mix of trochee and dactyl and anapest in the first quatrain, and it flows readily and easily. A similar mix characterizes the second verse. However, the third and fourth verses are more heavy and plodding, as befits the change of mood, the doubt of the adult. The stress moves forward here to the beginning of the line, underlining its importance to Hardy.

The date of the poem (1915) suggests that it is also a lament for a disappearing way of farming life. Machines had for some time been doing more and more of the work formerly carried out by animals as no one is going to imagine machines kneeling.

Hardy learned the tradition of the oxen kneeling when he was a child. He refers, in a letter to Edmund Gosse written in April 1898, to “the belief still held in remote parts hereabout, that the cattle kneel at a particular moment in the early hours of every Christmas morning just at, or after 12”.

The context of the poem is also significant. It was written and published in 1915, during the First World War. Many people who were clinging to residual beliefs became disillusioned as the harsh reality of war took away all the illusions of war. The note of hope seems at an odd with the pessimistic theme in most of his poetry but also makes sense in the context of his fondness for magical beliefs.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight