Primarily speaking of his philosophical outlook, Thomas Hardy was a man of intensity, and his poems are a reflection of that vehement personality. He is perhaps better known as a novelist, but his poems have been described as musical, powerful, and often mournful. The poem, The Darkling Thrush, is an honest example of his classic style. Through the bleakness of the landscape, the narrator muses over the problems of mortal life on the eve of the century’s finale. In this poem, we can observe the poet’s preoccupation with time, change, and remorse.

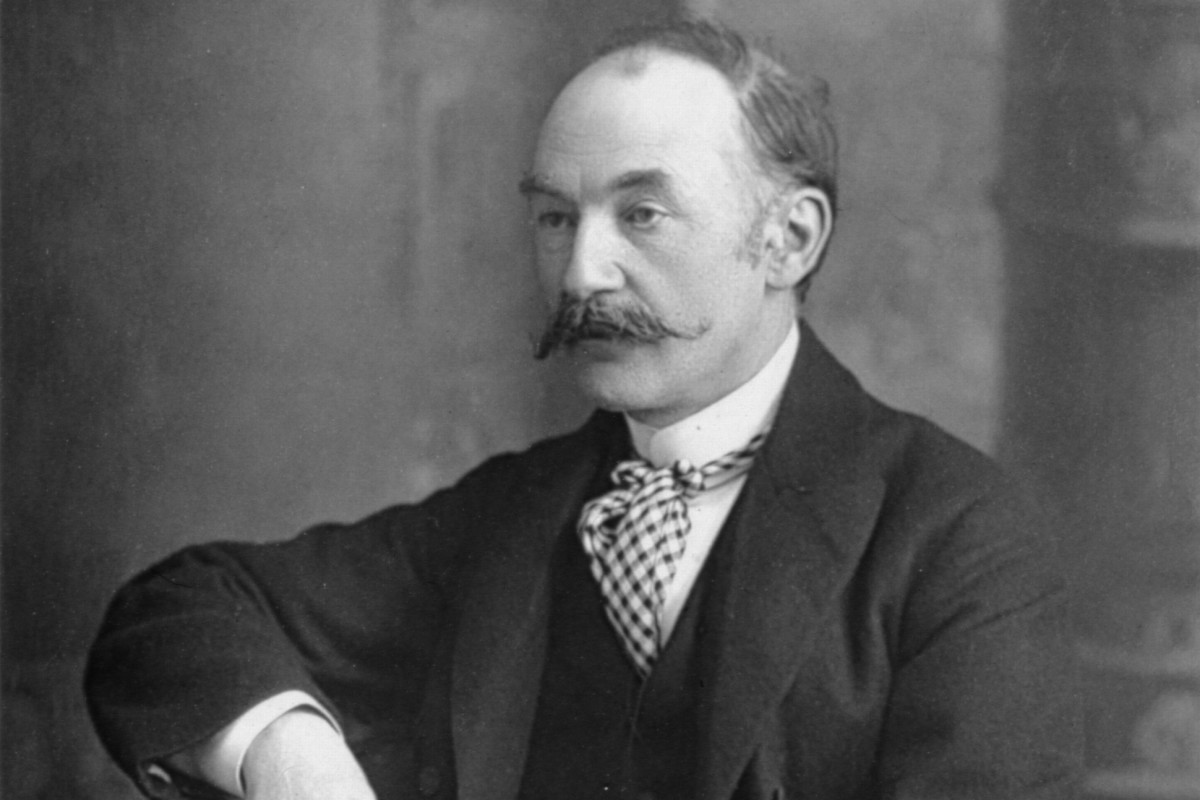

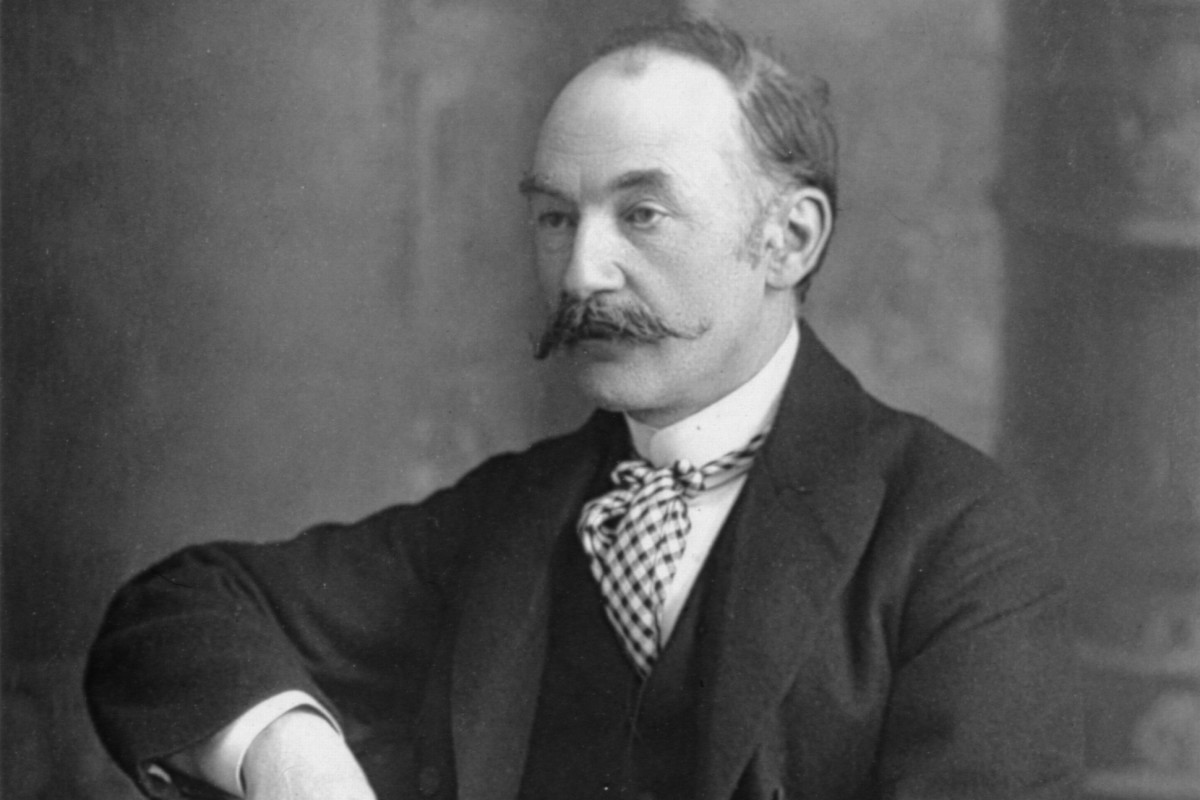

About the Poet:

Thomas Hardy, the novelist, and poet was born at Upper Bokhampton in Dorset in 1840. This birthplace has been later referred to as Wessex in his novels. As the son of Thomas Hardy Sr., a builder and a master mason, he was trained as an architect, but he soon gave up that choice of career to seek his true calling as a writer in 1874. In that same year, his first novel Far From The Madding Crowd was published to be an instant success. After he moved back to London in a few years, Hardy had already established himself as a reputable writer and was acquainted with London’s popular literary circles. In most of his writings, the elemental theme related the struggle of man against the force of nature, which according to Hardy, “rules the world and is basically neutral and indifferent to human sufferings.”

Although he enjoyed the applause and appreciation of London’s aristocratic and literary society, he also deeply resented the continuous criticism of reviewers of his “pessimism” and dereliction that apparently saturated his novels. Disturbed by this hostile outlook of his last two major novels led him to retire from fiction writing, and he was more inclined to write poetry in its stead, which anyways was his first preference of expression. Thereupon, he published eight volumes of poetry, containing over nine hundred poems between the years 1898 to 1928.

The Darkling Thrush: Summary and Explanation

Stanza 1:

“I leant upon a coppice gate

When Frost was spectre-grey,

And Winter’s dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

The tangled bine-stems scored the sky

Like strings of broken lyres,

And all mankind that haunted nigh

Had sought their household fires”.

The narrator of the poem, who is quite possibly the poet himself, paints a picture of the settling darkness that comes with the end of a day. The stanza begins on a dominant “I,” isolating the self from the world with a precise subjectivity so as to display a very personal outlook on the humdrum of daily life. Leaning on a copper gate, the poet watches the ghost-shaped frost swirling and falling, accumulating as the “winter’s dregs” that gives the sunset “the weakening eye of the day” a dismal appearance. The knotted “bine stems” embossed against the setting sky bring to the mind the grimy image of broken strings of a lyre. The poet notes that all the people who were about have gone home to seek the warmth of their “household fires.”

Stanza 2:

“The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The ancient pulse of germ and birth

Was shrunken hard and dry,

And every spirit upon earth

Seemed fervourless as I.”

In the second verse of the poem, the poet further delves into his solitary trance and begins to compare and connect the landscape around him to the century gone by. He brings the reader’s attention to the ragged contours of the land and collates it as the outlined “corpse” of the century. One by one, he illustrates a gloomy backdrop of degeneration by identifying the cluster of dark clouds as the “crypt” or the tomb of the dead century and the whistling wind of the cold winter as the mourning “death-lament.” The poet acknowledges the process of birth and germination as an ancient “pulse” that seems to have stopped due to the frozen hard ground and the cold, dry atmosphere due to lack of warmth and light; the inception of any form of life seemed impossible. The world around him appeared to have shrunken and “every spirit” as discouraged and passive as the poet felt himself.

Stanza 3:

“At once a voice arose among

The bleak twigs overhead

In a full-hearted evensong

Of joy illimited;

An aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small,

In blast-beruffled plume,

Had chosen thus to fling his soul

Upon the growing gloom.”

Through this melancholic evening, a voice arose amongst some gaunt branches and broke into a loud and radiant “even-song” of unlimited joy. An old frail little thrush bird with badly ruffled feathers had at once decided to through caution to the wind and had thus chosen to burst into a soulful cry in a desperate and obvious attempt to ward off the encroaching darkness. It was a heart-rendering effusion against the gathering gloom of the winter evening.

Stanza 4:

“So little cause for carolings

Of such ecstatic sound

was written on terrestrial things

Afar or nigh around,

That I could think there trembled through

His happy good-night air

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.”

In this last stanza, the poet is shaken out of his dreariness by the small little thrush bird’s joyful wail and remarks that even though there is so “little cause” to celebrate in such dreary circumstances, the bird makes its “ecstatic sound” regardless of its dull surroundings. He conjectures that there must be some mysterious cause for this uncorrupted sense of faith and hope in nature that the poet himself and all of mankind is oblivious to. That maybe happiness is more related to the inner self than the exterior influences. Even though the greater understanding of true serenity has not arrived upon the poet, he cannot ignore the possibility that there may be something beyond his rational wisdom that justifies that music of hope.

The poem was first published in The Graphic on 29 December 1900 and was originally titled “The Century’s End 1900”. The poem unfurls on closure and is a dark yet hopeful meditation on how death precludes birth, and the cycle is never broken. It is also haunting scrutiny of Victorian society and its intellectual progress contrasted by its socio-cultural failings. The poet experimented with meter and stanza forms producing a huge variety of verses. He also used colloquial language in his literary works, which fellow Dorset poet William Barnes partly inspired.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight