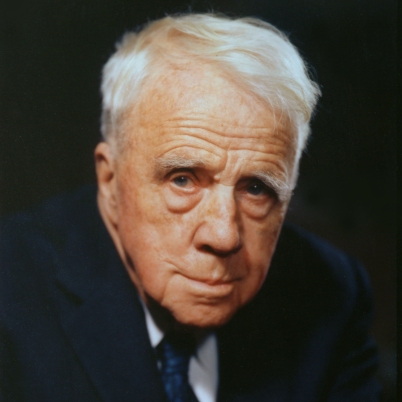

About the poet: Robert Frost, the most popular poet of America, was born in San Francisco, California, to Mr. William Prescott Frost, Jr., and Isabelle Moodie. His mother was a Scottish immigrant, and his father descended from Nicholas Frost of Tiverton, Devon, England, who had sailed to New Hampshire in 1634 on the Wolfrana. He is best known for his realistic depictions of rural New England Life. After graduating from the prestigious Harvard University, he went on to farm for his grandfather’s estate in Derry, New Hampshire. He used to write in the mornings.After that, he settled down in Beaconsfield, a small town outside London in 1912. His first book of poems A Boy’s Will was published in 1913. Frost was honored frequently during his lifetime, receiving four Pulitzer Prizes for Poetry. He became one of America’s rare “public literary figures, almost an artistic institution.” He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1960 for his poetic works. On July 22, 1961, Frost was named poet laureate of Vermont.

The setting of the poem: The poem is set in a birch forest where the narrator spots a birch tree or probably multiple trees bending down due to the ice storm. The forest is most probably in the countryside. Robert Frost has lived most of his life in the countryside. So, it’s no wonder that Nature would play an important role in his poems.

The mood of the poem: The mood of the poem is imaginative and dreamy. After seeing a birch tree bending down, the narrator starts imagining the possible causes for the phenomenon. The poet loves to think that the birches had been swung that way by the mischief of some adventurous kid. But as he himself had once been a swinger of Birches, he knows that such an effort would never bend them in a permanent way. Only ice storms can do that.

Summary of Birches

The poem consists of 59 lines in total. The poem is not in a stanza format, so we are dividing it into stanzas with thematic resemblances to help in our analysis of the poem. So, let’s start.

Line by Line Summary of Birches by Robert Frost

Summary, Lines 1-7

When I see birches bend to left and right

Across the lines of straighter darker trees,

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

But swinging doesn’t bend them down to stay

As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them

Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning

After a rain.

In these lines, the poet or the narrator, after having spotted a birch tree in a wood, starts thinking of the of the possible causes for the bending of the birch trees. First, he thinks of a boy who’s been swinging them and that may be the reason for the bending of the tree. But he soon realizes that only the act of swinging does not make the trees bend “down to stay” as “As ice-storms do.” So, indirectly he wants to imply the fact that ice-storm is the cause of the bending. Then the first-person narrator addresses the audience or the reader of the poem as “you” and wants the reader to remember having “seen them/ Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning/ After a rain.”

Summary, lines 7-13

[……] They click upon themselves

As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored

As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.

Soon the sun’s warmth makes them shed crystal shells

Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust—

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You’d think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

The poet goes on to describe the behavior of the trees as “[t]hey click upon themselves

As the breeze rises” and how they “turn many-colored/ As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel.” Soon after rising of the sun, the ice melts away shedding their crystal shells, “[s]shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust”. Evidently, the snows have frozen into crystals and when they melt, they crack and craze through their enamels or the outer layer. And after the initial melting, the shattered ice collects below the tree as if it were a pile of glass being swept into a dustpan. Then the poet adds a beautiful, allegorical line which heightens the beauty of the poem to a different level. He compares the broken snow crusts as “if the inner dome of heaven had fallen.”

Summary, Lines 14-20

They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load,

And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed

So low for long, they never right themselves:

You may see their trunks arching in the woods

Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground

Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair

Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.

In these lines, the poet or the narrator describes the birch trees “dragged to the withered bracken by the load,” under the weight of ice and snow. But they don’t break themselves as the poet is hopeful that they will “right themselves” although “bending low for long”. But sometimes, they might get permanently bent for long years, “trailing their leaves on the ground” or in other words, they get broken. Then the narrator compares these trees with their bending trunks “Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair/ Before them over their heads to dry in the sun.”

Summary, Lines 21-32

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

I should prefer to have some boy bend them

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

Summer or winter and could play alone.

One by one he subdued his father’s trees

By riding them down over and over again

Until he took the stiffness out of them,

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

For him to conquer.

The poet-narrator prefers to be in his fancy world as he comes to know about the hard reality of the bending of the i.e. the ice-storm. The poet is trying to avoid the reality here he is trying to escape reality. He likes to think some boy has bent them on his way back home after herding his cows. Some boy who is “too far from town to learn baseball,” whose “only play was what he found himself, / Summer or winter”. The poet-narrator likes to imagine the boy going out to his father’s orchard and climbing his father’s trees by “riding them down over and over again” until “he took the stiffness out of them,” leaving not a single tree left “[f]or him to conquer.” If we look at this line from a psychoanalytic point of view, then this can be seen as over-powering the father figure which every boy from his childhood tries to master in his unconscious mind.

Summary, Lines 32-41

[…..] He learned all there was

To learn about not launching out too soon

And so not carrying the tree away

Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise

To the top branches, climbing carefully

With the same pains you use to fill a cup

Up to the brim, and even above the brim.

Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish,

Kicking his way down through the air to the ground.

So was I once myself a swinger of birches.

The boy has now become an expert in bending the trees as he has learned “all there was/ To learn about not launching out too soon/ And so not carrying the tree away/ Clear to the ground.” He is meticulous in climbing the trees keeping his poise till he reached to the top branches. The narrator compares the pains he takes each time he climbs a tree with the filling of a cup to the brim or even above the brim. And after reaching the top, he jumps straight to the ground “with a swish”, “kicking his way down through the air”. All these remind the poet of his own childhood experiences when he, like the boy, used to swing birches.

“So was I once myself a swinger of birches.”

Summary, Lines 42-49

And so I dream of going back to be.

It’s when I’m weary of considerations,

And life is too much like a pathless wood

Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs

Broken across it, and one eye is weeping

From a twig’s having lashed across it open.

I’d like to get away from earth awhile

And then come back to it and begin over.

The poet narrator has become weary from his responsibilities as an adult in this tough world where one has to maintain a rational outlook. That’s why the narrator wants to go back to his childhood where once again he can enjoy all those little enjoyments. He feels lost. Now to him, Life seems to be like “a pathless wood/ Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs”. So, the narrator wants to get away from the earth for a while and then come back again to restart his life fresh. The strong sense of escapism is evident in these lines as common with the romantic poets like Wordsworth, Keats, Byron etc.

Summary, Lines 50-59

May no fate willfully misunderstand me

And half grant what I wish and snatch me away

Not to return. Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

The poet wants the fates to “half-grant” him a wish to go away from this world, from his responsibilities. The word half grant is of importance here as he does not want to go away permanently. He wants to return to this world as he thinks earth to be the right place for love.

“Earth’s the right place for love:”

As he doesn’t know any better place to go than earth. But then he thinks of going to heaven by climbing a birch tree “till the tree could bear no more, / But dipped its top and set me down again.” The poem ends on a lighter note stating that “[o]ne could do worse than be a swinger of birches.”

By Rohit Chakraborty

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight