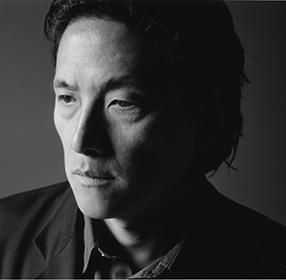

About the Poet:

James Mercer Langston Hughes (1902- 1967) commonly known as Langston Hughes was an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist. He was born in Joplin, Missouri. He was of African-American origin, his mother, Caroline Mercer Langston, was a school teacher and his father, James Nathaniel Hughes. He was a pioneer of the, then literary art form new jazz poetry. However, most importantly he is best known as the leader of Harlem Renaissance. Hughes became increasingly involved in radical politics and joined the American Communist Party because of its claim to represent all races equally in its working-class solidarity. He died in New York City at the age of 65 while suffering from prostate cancer.

About Mother to Son:

The poem Mother to Son by Langston Hughes was written in 1922. It was first published in the magazine crisis in December of 1922 and reappeared in Langston Hughes’s first collection of poetry, The Weary Blues in 1926.Mother to Son is a poem where the speaker is a mother who describes her hardships to her son by comparing her life to stairs. This poem is a monologue, a speech spoken by one person to another without interruption. The monologue is written in such a way as to suggest the natural speech of a woman who doesn’t pay much attention to formal grammar, but who can nevertheless say what she means.

The Setting of Mother to Son:

The poem “Mother to Son”, by Langston Hughes, is an uplifting, hopeful poem about never giving up. The main symbolism in the poem is when Mother compares her life to a staircase. She says, “Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.” By this, she means that life has not been easy, and her journey through life has been like climbing a staircase. As a black woman, her journey has been hard, and as she describes it, the staircase she has had to climb has “tacks in it”, “splinters”, “boards tore up”, “places with no carpet”, and is “bare”. It has not been a smooth and easy journey of life; the kind of life that a crystal staircase would provide. Instead, the Mother has led a life full of obstacles and hardships in her metaphoric climb up the stairs from birth to death.

She is hopeful for her son, and she encourages him to keep climbing like she has. The mother says to her son that life has not been a “crystal stair” – it has had tacks and splinters and torn boards on it, as well as places without carpet. The stair is bare. However, she still climbs on, reaching landings, turning corners, and persevering in the dark when there is no light. She commands him, “So boy, don’t you turn back.” She instructs him not to go back down the stairs even if he thinks climbing is hard. He should try not to fall because his mother is still going, still climb, and her life “ain’t been no crystal stair.”

Autobiographical Overtone of Mother to Son:

Langston’s parentage was of mixed race. His mother belonged to the influential, elite and politically active Langston family. She married James Nathaniel Hughes. However, Hughes’s father left them and later divorced his mother fleeing to Cuba to avoid the creeping racism in the United States. Hughes’s was raised in a number of Midwestern small towns before his father left. Afterwards, he was mainly raised by his mater grandmother. And he was highly influenced by the oral African culture and other African- American music which he grew up listening from his grandmother.

Since his parents got separated very soon after his birth. He saw the hardships his mother has to face in life in order to survive, which eventually separated them. He is well aware of the difficulties one has to face in life. As his, own life was not smooth we see the same things echoing in this poetry through the metaphor of stairs. The mother voice in the poem is voicing both his and his mother’s hardships.

Hughes was just beginning his career as a poet when he wrote this poem, so questions of what to write about and how best to forge his poetic voice and identity would be pressing issues for him. Would he strive to represent his race in poetry, and be a self-consciously black poet, or would he reject a racial poetic identity, as poets like Countee Cullen would try to do? Would he look to his African-American cultural heritage for inspiration, or was the black American experience, and its tradition of artistic expression, somehow outside the conventional boundaries of poetry? These were difficult questions for the young writer, and if we read “Mother to Son“ in terms of these concerns, we see the poet struggling to come to terms with them. In this context, the “son” of the title becomes not the reader, but the poet himself, and the poem suggests that the son’s frustration and despair are that of the poet, faced with the impossible task of writing poetry that truly speaks to and for the African-American experience. The poet–the “son” of African- American history and its artistic legacy of spirituals, blues, and jazz–looks to his “mother” for advice and the strength to keep going. Her response is stern, yet supportive: “So boy, don’t you turn back. / Don’t you sit down on the steps / ‘Cause you find it kinder hard.” The task he has before him is an arduous one, she says, but it is an important and necessary one. African-American culture and history keep moving and it is his job as the poet to record it; she’s “still climbin'” and he has to keep step.

His goal was to write a truly “Negro” poetry without perpetuating racial stereotypes. However, the poet’s “mother,” who speaks in the voice of the African- American teaches him he need not abandon that tradition in order to write poetry. All poetry, she says, need not be about “crystal stairs.” It can have “tacks” and “splinters” in it, “and places with no carpet on the floor.” It need not conform to white conventions in either form or subject — it can be “bare”–yet it need not ignore those conventions if they can be of use (In fact, the line, “And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair” is written in iambic pentameter, the most traditional of English poetic meters). The poet discovers, from listening to his mother-muse, a way to bring the African-American experience into poetry. He finds a way to move forward, to keep climbing.

Cross References to Mother to Son:

In another famous Hughes poem, entitled “The Negro Mother,” we find a similar speaker in a similar dramatic situation. . . .In “The Negro Mother,” which was written some years after”Mother to Son,” the speaker also tells her children about the “dark” and difficult “climb” she has faced in her life and suggests that her struggles will make those of her children easier to bear. But in the later poem, Hughes makes explicit the connection between the speaker and larger issues of African- American culture, as the figure of “The Negro Mother” comes to be seen not simply as an old woman talking to her children, but as, in some sense, the voice of African-American history itself, recounting its arduous struggle “that the race might live and grow.” In the same way, we can see the speaker of “Mother to Son” as representing a kind of collective voice, the voice of the generations of African-Americans whose troubled history–from the slave-ships, to the plantations, to Reconstruction, to the Great Migration to the urban North–“ain’t been no crystal stair.”

In the image of ‘stairs,’ we hear an echo of the Biblical story of Jacob’s Ladder (Genesis, chapter 28, verses 10-22), in which Jacob sees in a dream a vision of a celestial stairway upon which angels climb and descend between earth and heaven. In the dream, God tells Jacob, “This land on which you are lying I will give to you and your descendants [and] they will be as countless as the dust of the earth.” That land would become Israel and Jacob’s sons, the Israelites. This story held an abiding significance within the African-American Christian tradition–especially in the pre- Civil-War slave-holding South–as it spoke to a faith that, like the Israelites, black Americans too would be delivered to a “Promised Land.” The heavenly stairway became a powerful image of liberation and salvation, attainable only through suffering and faith in God. Hughes, along with most African-Americans of his time, would have been very familiar with the associations of Jacob’s Ladder with the struggle for freedom and equality of blacks in America, especially in its expression in one of the best-known traditional spirituals, “We Are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder.” This song, which would have been sung first in the fields and later in churches, involves a call-and-response between a singer and a chorus not unlike the relationship of Hughes’s mother and son. It speaks of climbing “higher and higher” to become “soldiers of the Lord,” includes the exhortation “Keep on climbing, we will make it,” and ends with the question, “Children do you want your freedom?”

In this light, it becomes easy to see Hughes’s mother figure as something like a racial matriarch addressing her scattered children and exhorting them to “keep on climbing” on their way to freedom. It also shows us how Hughes uses a single image, the “crystal stair,” to evoke simultaneously the painful history of blacks in America while pointing to the tradition of faith and hope that has sustained them through it all.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight