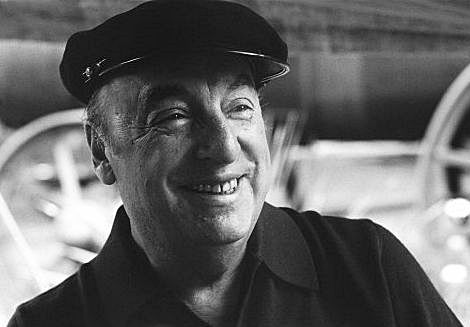

About the poet:

Percy Bysshe Shelly was born in 1792 to a Tory Squire who went up to Oxford only to be expelled in 1811 for bringing out the pamphlet on The Necessity of Islam. After his disastrous first marriage, he found a soul mate in Mary Shelley. He died by the element he liked best – water while sailing across the bay of Spezzia. Shelley’s first poetical work Queen Mab was published in 1813. In 1815 he wrote Alastor which is the tragedy of the idealist who seeks, in reality, the counterpart of his ideal. Shelley is considered as the greatest lyric poet of England. Prometheus Unbound was the first dramatic poem of Shelley which distinctly showed that one of the greatest lyric poets of the world has been produced. The lyrics of Shelley not only articulate the most radical revolts of his time but of all times to come. He was above all a humanitarian. Love was the root and basis of his humanitarianism. He was a devotee of liberty and hated all forms of oppression. The prophetic notes, the hope in a golden age, the regeneration of mankind, the Millennium underlie also the major poems of Shelley. Shelley has been described as the most visionary of all English poets, and his poetry has been described as ‘the fabric of a vision’. On the representation of his vision in his poetry, he does not completely shut himself from reality. In fact, he often comes in conflict with the harsh facts of real life, and much of his poetry is the expression of that struggle to transcend reality. His philosophy mainly deals with the problem of evil in the universe.

About Ozymandias:

The great sonnet was published on 11th January 1818 on page 24 of number 524 of Leigh Hunt’s ‘The Examiner’. It had apparently been written barely two weeks earlier. The occasion of its composition is now well known. At his house near Marlowe on Saturday 27 December 1817, the day after Boxing Day, Shelley entertained Horace Smith (1779-1849), whom he had met at Leigh Hunt’s the previous year. Smith was equally talented as a financier, a verse parodist, and an author of historical novels. The talk seems to have drifted around to Egyptian antiquity and to Diodorus Siculus, whose arrogant epitaph ascribed to Ozymandias “had become virtually a commonplace in the romantic period;” and a friendly competition ensued in which each writer was to produce a sonnet on the subject of “Ozymandias, the King of Kings.”

The Theme of Ozymandias:

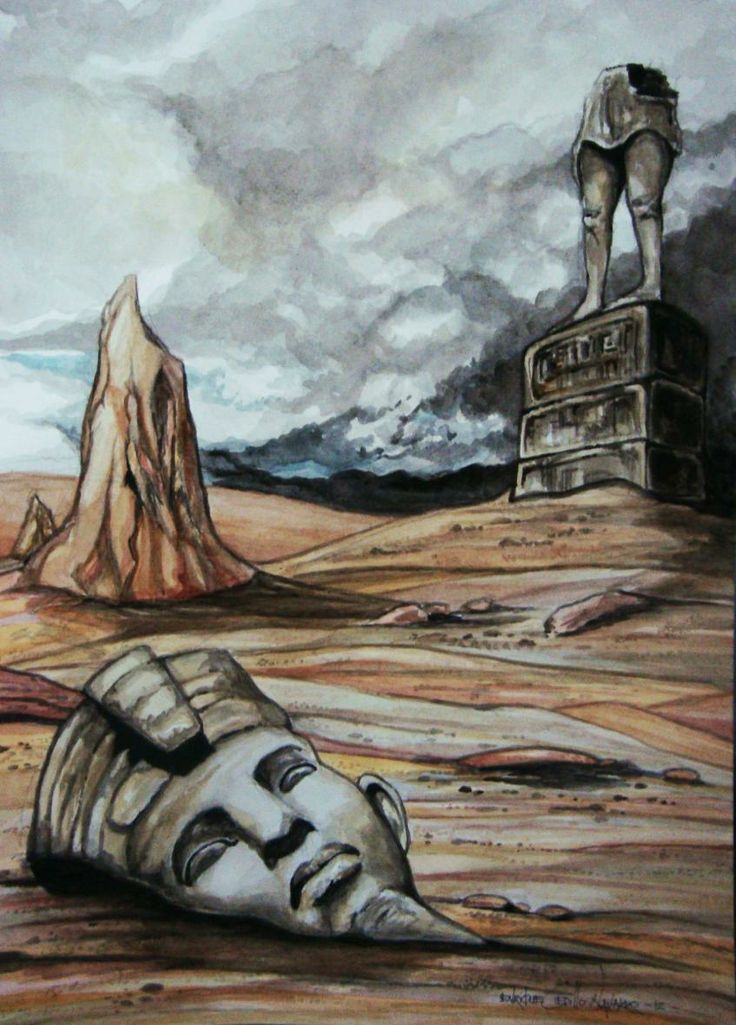

Why does the speaker or poet not describe directly the fallen statue he has seen or sees? One answer, by far the most familiar, is that the traveler, “a reliable fellow,” in Desmond King-Hele’s urbane judgment, “quick to observe relevant detail and not too wild in interpreting it,” lends credibility to the poem’s report. Another, less often heard but feasible, is that by displacing the testimony from first to second hand, Shelley introduces what otherwise would hardly occur to us: the possibility of doubting its validity. For while the removal depersonalizes the account in a way Shelley, that pre-eminently personal poet, apparently found intriguing, voices other than the poet’s or those that pass for his are almost inevitably less automatically credited than his own. This question, however, like the issue of sources, is ultimately more interesting as a reflection of the questions and issues the poem itself raises and vies with than for the answers either give. For what is quite undeniable is that? whether at the price or added profit of credibility – the poet “distances himself from the poem’s subject by having all details supplied by some unnamed traveler.”

One point of the poem, surely, the one on which its irony – indeed all irony depends, is that texts or statements can be read in more than one way. Most obviously this refers to Ozymandias’ reading of his achievement and the poet’s apparent reinterpretation of it in the light of time’s triumph and the surrounding void. But there are more than two readers here and more than one text to be read. There are two readers of events who speak the poem: the traveler and the “I” (we will call him “Shelley”) who met him, heard his words and recorded them. There are two more readers in the poem to whom at least one of the first pair, the traveler, refers: Ozymandias and the sculptor who “well those passions read Which yet survive. …” And there is a fifth reader outside the poem whose job it presumably is to read, interpret, and understand them all.

The Tone of Ozymandias:

This distance, supported by the detached tone of the poem, is markedly atypical of Shelley, and it provides another explanation for the poem’s neglect among writers interested in Shelley’s poems chiefly as constituent entries in a coherent canon representative of the poet and the man. There may be much to learn about the poet Shelley from the seemingly aberrant detachment of this poem. But my immediate concern is with “Ozymandias” and with the concepts of distance, postponement, filtering, interpretation, and reliability that pervade and characterize it. The traveler is but the most obvious manifestation of the poem’s preoccupation with such matters, the surface extrusion of a deeply stratified formation that is the poem.

Conclusion:

The apparent meaning of the poem is itself postponed until the last lines, even a bit beyond their reading to the delayed grasp of the ironic disharmony between the inscribed boast and the leveling sands that follow and erode it. Not until we arrive at the closing words of the poem and perhaps beyond them do we realize that process is the point, that knowledge is a matter of postponement and delayed recognition. This principle of postponement, however, is not postponed. It begins with the interposition of the traveler in the first line of the sonnet and is quickly thickened by the syntactic organization of his introduction and first words.The description commences after a portentous colon pre pared by more than a line of verse, and it is marked by clipped adverbial phrases and pauses that hesitantly detail the description yet thwart our arrival at its main subject. The fragmented construction is doubtless a verbal replication of the fractured statue it describes. But it is also part of the system of filtering postponements that steal not initial but delayed and considered attention from the simpler message. Or rather, it shifts attention from the obvious substance of the moral to the conditions of its realization. No less than the judgment of Ozymandias, then, “Shelley’s” and our own is subject to the ravages of time. More fully than we had guessed, it is all? As the poem’s technique implicitly avers? A matter of postponement, distance, and added perspectives. It is from such layered distances, the scholars tell us, that Shelley arrived at his poem and the larger ideas it seems to offer us. Travellers of another kind, we must wind the same way.

The description commences after a portentous colon pre pared by more than a line of verse, and it is marked by clipped adverbial phrases and pauses that hesitantly detail the description yet thwart our arrival at its main subject. The fragmented construction is doubtless a verbal replication of the fractured statue it describes. But it is also part of the system of filtering postponements that steal not initial but delayed and considered attention from the simpler message. Or rather, it shifts attention from the obvious substance of the moral to the conditions of its realization. No less than the judgment of Ozymandias, then, “Shelley’s” and our own is subject to the ravages of time. More fully than we had guessed, it is all? As the poem’s technique implicitly avers? A matter of postponement, distance, and added perspectives. It is from such layered distances, the scholars tell us, that Shelley arrived at his poem and the larger ideas it seems to offer us. Travellers of another kind, we must wind the same way.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight