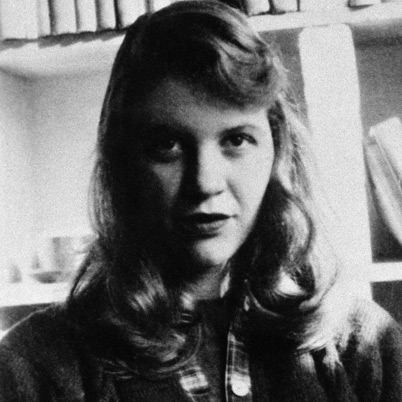

In this intensely self-dramatizing poem, she wrote shortly before her own suicide in February 1963, Plath adopted highly strained metaphors to describe her psychic state. “Lady Lazarus,” written in the fall of 1962, begins with a comparison between the poem’s speaker and the Jews tortured and killed in World War II:

A sort of walking miracle, my skin

Bright as a Nazi lampshade,

My right foot

A paperweight,

My face a featureless, fine

Jew linen.

Plath pushes beyond poetic convention in her choice of metaphors, assaulting the reader’s sensibilities with the lurid violence of her images. As Jon Rosenblatt notes, Plath’s comparison of the sufferings of her speaker to “the sadistic medical experiments on the Jews by Nazi doctors and the Nazis’ use of their victims’ bodies in the production of lampshades and other objects” is intended not to make realistic historical comparisons but to “draw the reader into the centre of a personality and its characteristic mental processes.”

Though some readers have objected to what they see as Plath’s misappropriation of the holocaust for use in a poem about individual suffering, Rosenblatt argues that imagining her own psychic drama against the backdrop of Nazism is justified as a means of universalizing the personal conflict. Nevertheless, the question of Plath’s direct appropriation of traumatic historical imagery remains a troubling one in poems such as “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy,” and it raises fundamental questions about the use of historically specific imagery or personae in the service of personal or “confessional” poems. Does the fact that Plath herself was not Jewish, for example, have any bearing on the legitimacy of her use of the holocaust as a defining metaphor for her own struggles? To some it has a lot of bearing to some none at all.

Plath subordinates the poem’s “confessional” aspect (its status as personal or biographical revelation) to its dramatic structure. Though the poem deals in a general sense with Plath’s own suicide attempts and their aftermath, the personal details are left vague, and the poem’s speaker focuses more on the creation of her mythic persona. The cultural complexity of this created persona is suggested by the title’s conflation of the biblical Lazarus (who rises from the dead in an ironized version of the failed suicide) and the “Lady” (with echoes of Lady Godiva, the Madonna, and various other figures from literature and fable) who becomes legendary in her suffering and ability to withstand various forms of torture.

If the title is not immediately seen as comic, the grotesque comedy of the poem soon becomes apparent both in its form and in its presentation of the persona. Lady Lazarus compares herself to a carnival freak, whom the “peanut-crunching crowd / Shoves in to see.” She feels herself to be on display, both as a suicide and as a woman: later in the poem, she describes the viewing of her scarred and emaciated body as “the big strip tease” and as a theatrical “comeback in broad day.”

At this point, Plath uses the form of the poem – and in particular the repetition of rhyming words – for a darkly comic effect:

There is a charge

For . . . charge

For . . . heart –

It really goes.

. . . large charge

For . . .

. . . blood

Or a piece of my hair or my clothes.

Plath’s use of the three-line stanza – as in other late poems like “Ariel” and “Fever 103” – carries echoes of the terza rima form of Italian tradition; but Plath’s use of the stanza provides only a general structure for her experimentation with a variable rhyme scheme and metrical pattern.

Most of the rhymes in the poem are off-rhymes (put/brute; goes/clothes; stir/there), and the pure rhymes often work through repetition of the same word or through combinations of internal and end rhymes that create a kind of syncopated feeling (“I turn and burn, / Do not think I underestimate your great concern”). In the above passage, the word “charge” is repeated four times within five lines, the last time accentuated by the internal rhyme with “large.” This kind of insistent rhyme highlights the pun implicit in the word “charge”: it is both an electrical charge (consistent with the imagery of lamps, burning, and the body as machine) and the monetary charge for those who want to see Lady Lazarus. The lines mock the reader, who, like the “peanut-crunching crowd” which pays to see Lady Lazarus, is implicated in the voyeuristic act of watching Plath’s “act” of self-revelation, a kind of biographical “strip tease.”

The reader is drawn into the poem by this conceit, invited to watch, listen, and even touch the woman, who is herself reduced to a set of mechanized body parts: her heart, for example, is like a wind-up toy that “really goes.” The sound of the words here – especially the repetition of the harsh “ar” sound in “charge,” “scars,” “heart,” and “large” – adds to the brutally ironic tone of the passage. This disturbing effect is intensified by the relatively short lines and the use of meters more typical of light verse (for example, the rocking anapaests of “For a piece of my hair or my clothes”). Throughout the poem, Plath not only portrays her own torment, but parodies her attempts at suicide. This self-parody, however, is mixed with a sense of pride at her ability to manipulate both herself and her readers.

Plath’s persona of a performer in the poem – whether it takes the form of stripper, sideshow freak, or vaudeville comedian – allows her to declare herself a success. The implicit comparison between Plath as poet and as suicide is clear in the following lines:

Dying . . . else.

I do . . . well,

I do . . . hell.

I . . .real.

I . . . call.

Plath’s virtuosity as poet – which she displays in her manipulation of voice, image, form, and rhythm throughout the poem – is mapped onto her skill at “dying,” which she perversely claims to do “exceptionally well.” By writing poems about her own suicide attempts, Plath is also selling herself as poet to the reader.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight