From the very first line, the poem proposes to do what its title “A Valediction of Weeping” evinces; Donne composed this piece as a valedictory note of absence from his wife owing to travel abroad. The poem is centred on the narrator’s central thematic entreaty of taking stride in this temporary leave-taking, rather than indulging and wallowing in tears which will only hinder their well-beings. The poem emphasizes the need for forbearance and patience, albeit from a romantic angle, and points at the need for tolerating much of the inscrutable pangs of separation, plaguing both the narrator and his wife, presumably, with a resigned acceptance.

The initial of the three nine-line stanzas commences with the narrator almost pleading with the betrothed to let him cry, to expiate his own grief at the prospects of impending loneliness and extrication from his wife. In an unexpected twist, the poet monetarises the outpour, likening his outpour of tears to that of coins, which carry within them the imprint of his lover’s face, “stamped” within. His face, in turn, is bestowed value by his lover’s presence in his tears, and is impregnated with her presence.

Though they are “tears of grief” as the narrator candidly confesses, and “emblems of something more”, something unstated, their descent across his cheeks reminds him of how their bond is “dissolved” (quite literally) thus, and how the two could hypothetically be reduced to “nothingness” (-es). The image of the shore, which is littered aplenty across Donne’s repertoire, recurs here, to stand for the symbolic loneliness shared by the two extricated lovers.

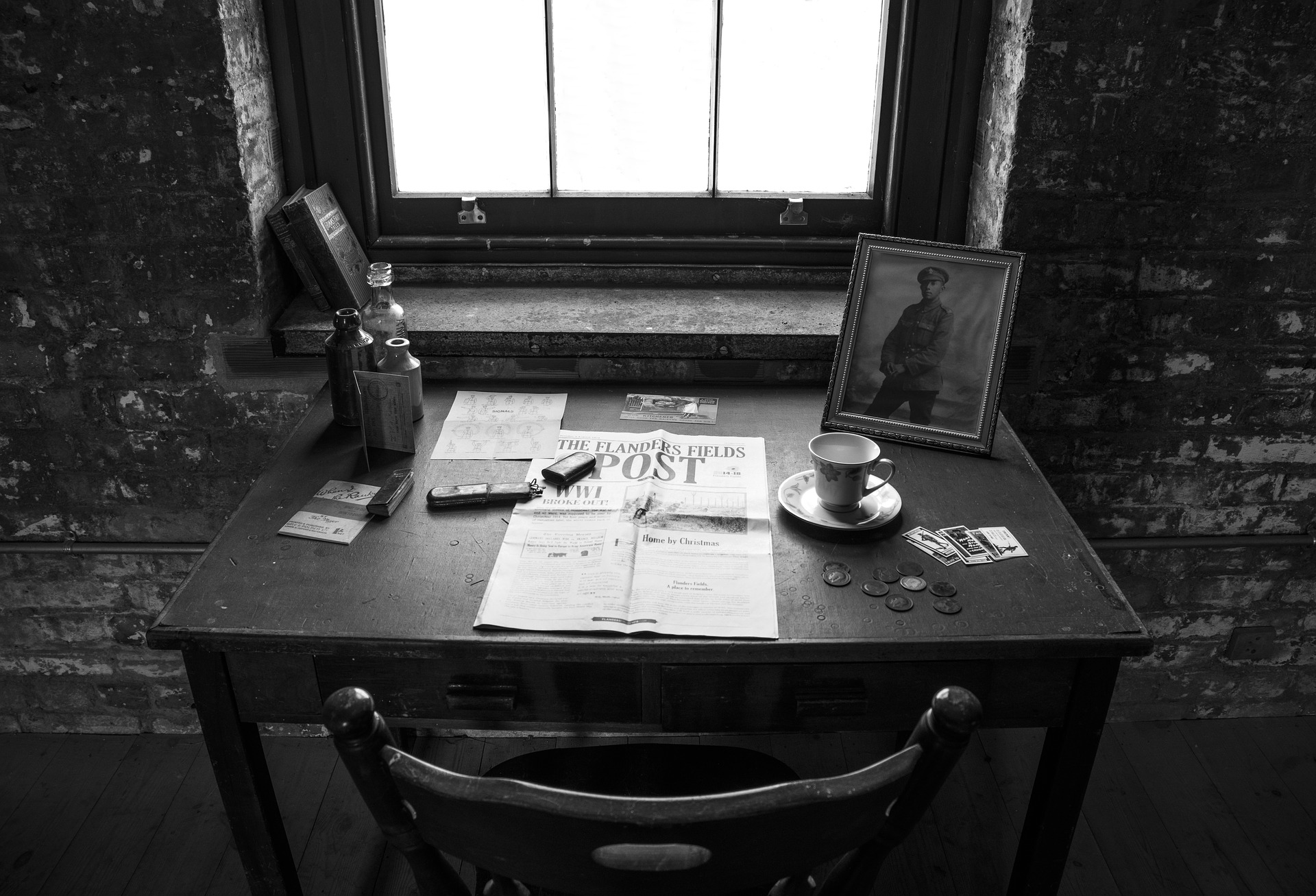

The succeeding stanza deploys the metaphor of cartography, which is of map-setting, which gains significance in lieu of the contemporary exploits of the seas and the distant, hitherto unexplored worlds by adventurers and imperialists with motives. Such revelry in discovering new lands had been facilitated only by technological advancements, including cartographic advancements. The mapmaker is imagined here as very arbitrarily placing the “continents” on the form embodied in the globe, and thus constituting the planet with the seven continents and seas and oceans, as we know it.

Unlike this effort which transforms the vacant into a contained space of signification, the narrator claims that each of his tears, howsoever trivial, when comes in contact with his wife’s tears, will overflow the world. The image here is clearly destructive, one proffering deluge as its end, in opposition to the constructive impetus of the mapmaker. And what is on the receiving end of this deluge, this untempered destruction is his “heaven”, i.e. his relationship with his lover (an instance of the use of hyperbole). All he can do, once again, is ask her to not shed any more tears.

In yet another instance of the use of a hyperbole, the narrator likens his lover to the moon pulling the tides of the sea, (though, she is, “more than” the moon in her capacities) and deems her as being capable of drowning him in her own tears by pulling the current in the teardrops. The line “Weep me not dead…” introduces a note of uncertainty that is to soon transmute into cynicism, if not crypticism at the very end.

The poignant note which the expression of sorrow had sounded so far, suddenly is jolted by the incorporation of death, of the possibility, rather of one of the lovers killing the other unintentionally, of one f their deaths being attributable to the “love” (the tears are only a manifestation of the love) of the other partner. The anxious narrator furthermore insists his lover to decline from teaching the sea to drown him. The portrayal of the beloved female figure in terms of Nature and its elements is hardly new, but one should take heed of the fact that Donne’s “naturalization” of their mutually shared and affected love comes at the expense of imposing certain facets and tenets on her unexpounded identity.

This silences the woman character, who does not appear as a subjective being with any individual agency of her own (apart from what has been inferred onto her by the graces of the male poet), and furthermore posits her (I what seems like a tired cliché from the modern reader’s perspective) as being involved with, or corroborating with the underlying conspiratorial forces of nature. There is a sly indictment at the supposed capacity of women as organic, fertile, relatively more earth-bound beings potentially capable of wreaking havoc upon human lives by dint of such inexplicable powers.

The poem further testifies this argument; it is inevitably the woman whose tears, much to the chagrin and apprehension of the narrator, will drown not only the world, but him as well; seldom does the poet attribute any such potential violence onto his tears, his emotions and reflexes. The wind, the reader is summoned to observe, can find the exemplary impetus in the woman’s unabashed outburst of emotion. Like her tears, her sighs are potent enough to cause sea-storms which may hasten his death.

Love and death, by now, have been settled into an uncomfortably close proximity, to the point that the latter seems not only inevitable, but also as having been consequated by love. There is a note of ambivalence or even menace in the concluding couplet, which seems to be ominously reminding the ailing lover that since she sighs his breath (and vice-versa), and is one with him, she two will succumb to death, in case he does. It could be read very simply as the narrator asking his beloved to desist from sighing one another’s demise, for that would be mutually destructive for both of them. The shedding of tears, as acceptable and legitimate an emotional response as it is, should be minimized in order to not hasten their deaths, with thoughtless cruelty.

Traditional interpretations of the poem show the poet as emerging as the voice of necessary reason presiding at its denouement, as bequeathing the crucial pragmatic lesson to his lover to mitigate her emotions and not compound their individual agonies by crying. But, this apparent attempt at finding that resolve of mind to tackle the odds does not answer our query as to why the poet injects such a virulent sensibility of death, and of dying, into the prevailing rhetoric.

Donne had famously equated orgasm with what he called “small death”, and the intertwining of Eros and Death are concepts we are all familiar to. But Donne’s supposed valedictory attempt makes us see how the tears are unavoidable, and how, in absence of the requisite forbearance and resilience of mind (which he emphasizes on cultivating), the tears can translate into loss, or even death. The catharsis the narrator had in mind when he wanted to shed his tears in front of her, remains denied when it comes to discerning the motif of the poet and his perception of his relationship with his wife.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight