The poem features amongst a collection of twenty three short prose meditations dedicated to Prince Charles, son of King James I, and contemplates on the meager but indispensable role of human beings in the scheme of a universe, incomprehensible, unfathomable to him barring the knowledge that it is governed by a supreme benedictory being. Borrowing the bell-metaphor he had so dexterously deployed in the previous (sixteenth) meditation, the poet muses on the great ebb and tide of life and death that sweeps the entirety of existence, and thinks of himself as the dead, but still integrated into the network of God’s machinations.

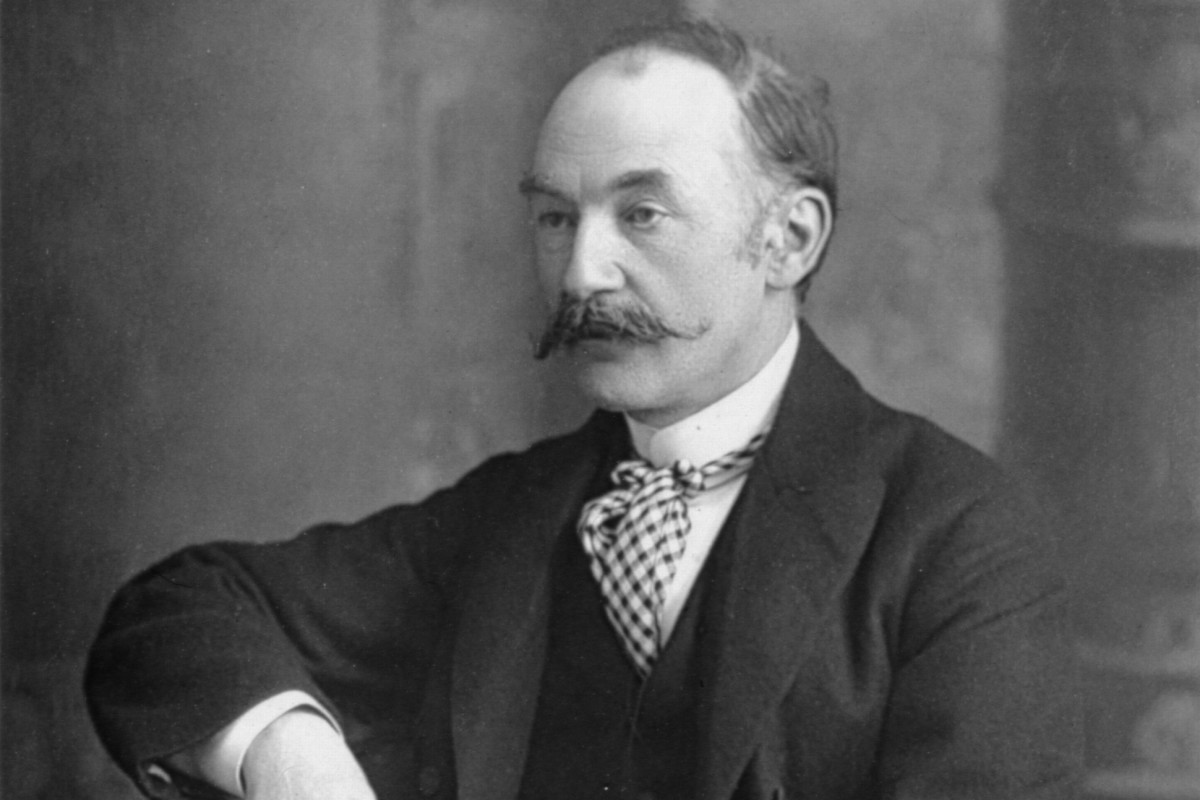

He had heard the tolling of the bell from his neighbourhood church day after day in the previous meditation, whilst resting on bed on account of physical illness. Aloof and dejected, he uses this pensive mood to reflect on himself as being one of those dying men, transitioning from one life to the next, and suddenly gives himself over to thinking that in spite of his innocence of the fact, people have caused it to toll for him, i.e. in his remembrance.

The initial lines of the meditation reveal the existence of a masochistic streak in his personality. It is almost the gusto of this unforeseen thought that compels him to identify himself as that dying man he imagines he is in the perception of the visitors, who keep a safe distance from him to avoid contamination.

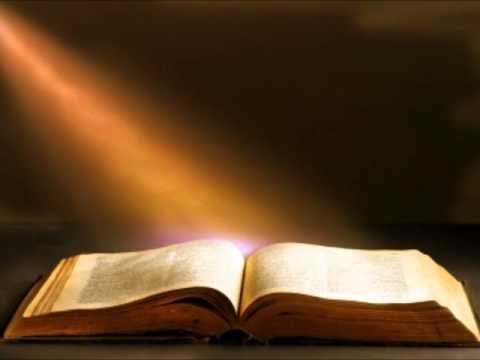

The invocation of the Catholic Church is perhaps an attempt at self-consolation, to ensure that he would not be, in this ailing state, deprived of God’s endless mercy, since “All that she (the Church) does, belongs to all.” The stranded, diseased body that prompted such a metaphysical realization in the commencing lines now transmutes to adopt or become a part of the Body of Christ, which is the inheritance of the entire Christendom, all of whom are deemed equal in His eyes. The ritualistic tradition of the Eucharist that takes place in the church is precisely a symbolic reminder of how all devotees partake in His eternal grace by literally ingesting the blood and body of Christ.

Hence, as the Bible insists in its dictum, men and women in their mortal lives should be kind and responsible toward one another, since they are all His children, and are only waiting to become one with him in the subsequent life. The dejection of dying is for a moment surpassed by the joy of realizing this universality which spurs the narrator to think that the death of an individual does not tear a chapter out of “the booke” of which He is “The Author”, but rather ensures that it is “translated into a better language.” Regardless of whether it is age, sickness, war or justice that is responsible for the obliteration of each life (all of it being inevitable by presupposition), the Divine Maker has a hand in all of these “translations”, which grafts onto Him the role of a conscientious and capable artist, more precisely that of a “library-keeper”.

What this eventually leads to is the understanding that the bell tolls not for one individual, but for the sake of all who have the ears to hear it, who realize and can internalize the implications of being a part of the same supremely manifested and intersubjective plan. Moreover the tolling of the bell is also a symbolic reminder for the faithful to arrange their own affairs on this planet, as preparations for the subsequent sojourn. In being connected to one another, the individual should espouse acts of charity and practice the transparency that will ensure spiritual rewards in, and characterizes the forthcoming life.

The narrator extends forth this argument in saying that whilst religious orders quibble over their rights to first chanting in the morning, one can equally commit themselves to the evening prayers, provided one understands the full implications of the chime of the bell. That sound serves as the source which will bind together all who come to hear it, and settle any differences between religious groups, sects, people of varying affiliations and states. In Donne’s words, the bell also passes “a piece of himself out of this

world” for those capable of discerning it.

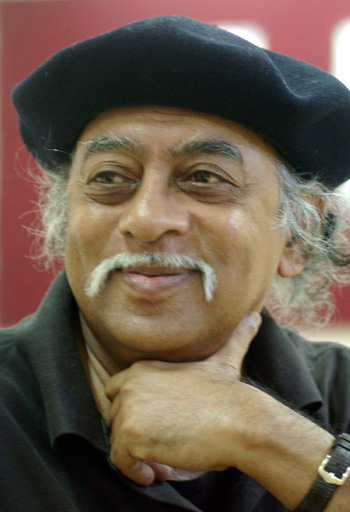

“No man is an island, entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main” is perhaps one of the most recalled f lines from Donne’s oeuvre, and aptly so, for it reminds us not only of the intersubjectivity we have been talking about so far, but also endows us with a certain benign humility about our origins, which we are led to believe, are not so different from our ultimate destinations. Any individual human being, contrary to any antagonistic opinion he might be entitled to, cannot extricate himself from the rest of the living, breathing cosmic continuum and pretend to be complete of its own position, of the integrity of its stance.

It is implausible for one man to grow and thrive in society without the love and affection of his fellow-citizens. Furthermore, the myth of self-sufficiency which has long been propagated for the “western man” as a master of nature as well as of the self is demolished at the very onset of the meditation.

Under these circumstances, any death of any one man cannot, for the narrator, be held as being circumscribed within the immediate family. The death of any one man sends out a ripple onto the world, which is diminished by his “deletion”, and the poet sees that as a tragedy for the human race. The “involvement” with mankind that Donne projects onto the narratorial voice is his and it is a politically charged commitment to humanity that is being propounded here.

The personal is political and vice versa, and boundaries can only sustain differences so far. The death of a man does not signal the arrestation of that chapter in the book, but rather prepares the ground for the conversional transcendence of that chapter in his life. The bell which tolls in silent remembrance of the deceased is there to remind all of us that it is our loss. The collective “thee” refers to the unified race of humanity across all divisions and prescriptions of race, gender and so on, and resonates with the chiming of the bells.

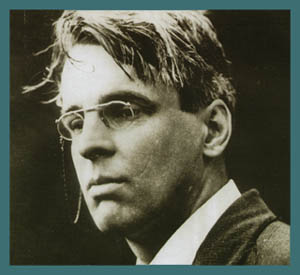

There is arduousness in how he asks us to accept the truth of pain, and grow from and within it, as opposed to be degraded by the consequential misery. That, he insists, is the kind of “affliction” that prepares us for God’s life and company. Ardour and tribulation will but pave the path for glory and happiness. The poet unexpectedly deploys materialistic metaphors to hone in an intensely felt point of spiritual significance.

Affliction lying in one man’s bowels has been likened to gold inside a mine, but the validity of this comparison can be sustained insofar as the poet hearing the death bell for that afflicted individual realizes that the “golden” opportunity for him to partake in a fellow man’s pain has arrived, and that it should ideally spur him to take recourse in God, unswerved in his faith, and in spite of whatsoever affliction await him in the dark future.

Some online learning platforms provide certifications, while others are designed to simply grow your skills in your personal and professional life. Including Masterclass and Coursera, here are our recommendations for the best online learning platforms you can sign up for today.

The 7 Best Online Learning Platforms of 2022

- Best Overall: Coursera

- Best for Niche Topics: Udemy

- Best for Creative Fields: Skillshare

- Best for Celebrity Lessons: MasterClass

- Best for STEM: EdX

- Best for Career Building: Udacity

- Best for Data Learning: Pluralsight